Earlier this week, HDB announced a few changes regarding income assessment and housing subsidy. The changes took effect from 9 May 2023 onwards — the same day the HDB Flat Eligibility Letter (HFE) replaced the HDB Loan Eligibility (HLE) letter.

Among the changes, the ones that caught our eye are these:

- How the HDB grants are distributed and used

- The essential occupier being treated as a second-timer in the next flat purchase

We don’t know about you guys, but to us, they seem like a form of cooling measure for public housing.

Major change #1: How the HDB grants are distributed and used

Essentially, from 9 May 2023 onwards, HDB grants are distributed equally to the applicants and essential occupiers (which HDB refers to as core occupiers in their press release). They will get the grants in their CPF Ordinary Accounts (OA).

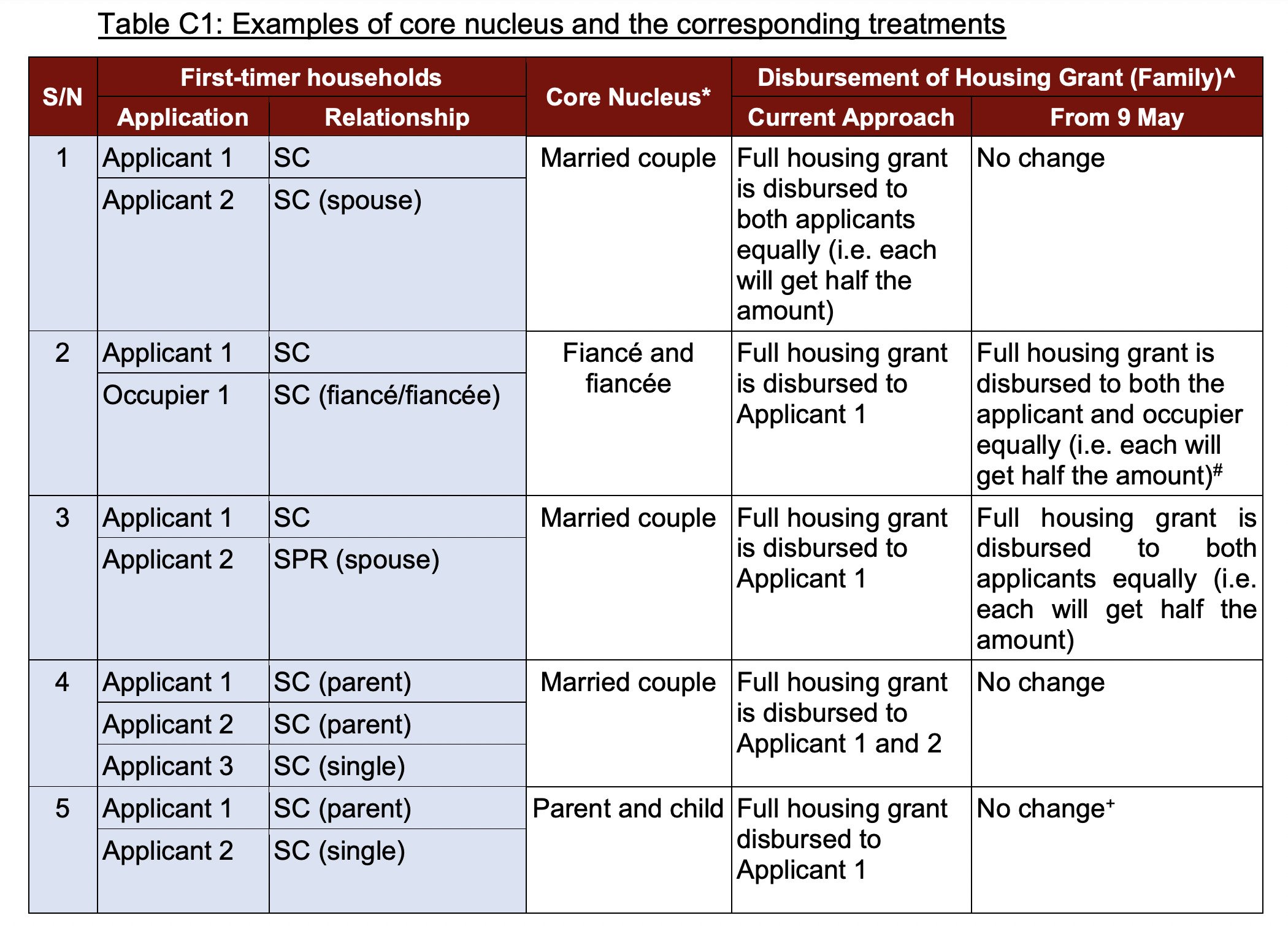

This table from HDB summarises how the grants are now distributed.

Previously, only those listed as the owners will receive the grants in their CPF OA.

What’s more, PRs will now receive a share of the grants. Before 9 May, the grants would only be credited to the SC’s CPF OA.

This means that for an SC/PR household buying a 4-room resale flat, they’re entitled to a CPF Housing Grant of S$70,000. The amount will be split between the OA of the SC and PR, i.e. each will get S$35,000.

Perhaps the most significant change is that even though the essential occupier receives the grant, they won’t be able to use it to offset the flat purchase, unless they’re listed as an owner.

Alternatively, they can use it for the next HDB flat purchase, but not for private property purchase. (The silver lining is that the grant will earn you 2.5% interest while it sits in the OA.)

How it’s akin to a cooling measure

Before this change, the government announced during Budget 2023 that the CPF Housing Grant for resale flats will be increased, from S$50,000 to S$80,000 for a 4-room flat or smaller. This comes after soaring prices in the resale market and rising concerns of housing affordability in the last couple of years.

One possible effect of the increase in grant amount is that it may have encouraged sellers to push up prices, since the buyers could better afford the purchase.

But with this new change in the usage of the housing grant, households with one owner and one essential occupier can only use half of the grant amount to offset the flat purchase.

Let’s say an owner-essential occupier household is buying a 4-room resale flat and is eligible for an S$80,000 grant.

With the change in usage and grant distribution, each will get S$40,000. But since only the owner’s share of the S$40,000 grant can be used for the grant, this may get them to rethink their flat purchase. They may instead want to settle for a flat with a lower price.

This may help slow down the resale price increase coming from these households.

Hang on, what’s this “buying an HDB flat as an owner-essential occupier household” all about?

Here’s something not a lot of people know. When buying an HDB flat as a household together with the spouse, parent or child, we’ve heard of stories where only one person is listed as the owner, while the other is the essential occupier.

(This is different from the application, whereby you have to apply as a family to be eligible for public housing if you’re not buying as a single.)

An essential occupier (or the core occupier, according to HDB) refers to a household member that’s listed in the flat application to form a family nucleus to help you qualify for a flat. The essential occupier can also help you increase your chances of getting a BTO queue number, and qualify for grants. They can be your spouse, child or parent.

Like the owner, the essential occupier will have to meet certain conditions, such as

- Not having any interest in any private residential property before the HDB flat purchase

- Physically occupying the HDB flat during the MOP

- Not allowed to own any other residential property during the MOP

- Being allowed to buy or invest in private property after MOP

The main difference is that they don’t have any ownership and share in the flat. This means that after the MOP, they can buy private property without incurring the 20% ABSD.

Meanwhile, the main owner can still keep the flat.

See where this is going?

With the changes in the usage of the grants, these owner-essential occupier households can still go ahead with their plan of buying a private property in future, after their MOP has ended.

But with only half the grant received that can be utilised, their affordability will be reduced.

That is, unless they decide not to follow through with the owner-essential occupier plan, and buy the flat as co-owners instead. If they still want to buy private property in future, they have to sell the HDB flat after the MOP so that they won’t incur the ABSD.

Major change #2: The essential occupier will be treated as a second-timer for the next flat purchase

Another implication of the essential occupier receiving the grant is that they will now be treated as a second-timer for the next flat purchase.

This is because they’re also deemed to have received a housing subsidy.

(The exception to this rule is parent-child households. The first-timer child, whether they’re listed as a co-applicant or essential occupier, won’t be considered to have enjoyed the subsidy this time. See the table above for more info on this.)

Previously, they would be considered first-timers. First-timers get more benefits when buying public housing, whether it’s BTO or resale.

For starters, most of the BTO and SBF flat supply is allocated to first-timers. During the application stage, households with first-timer and second-timer applicants are considered first-timer families, allowing them to get the same benefits as those who are both first-timers.

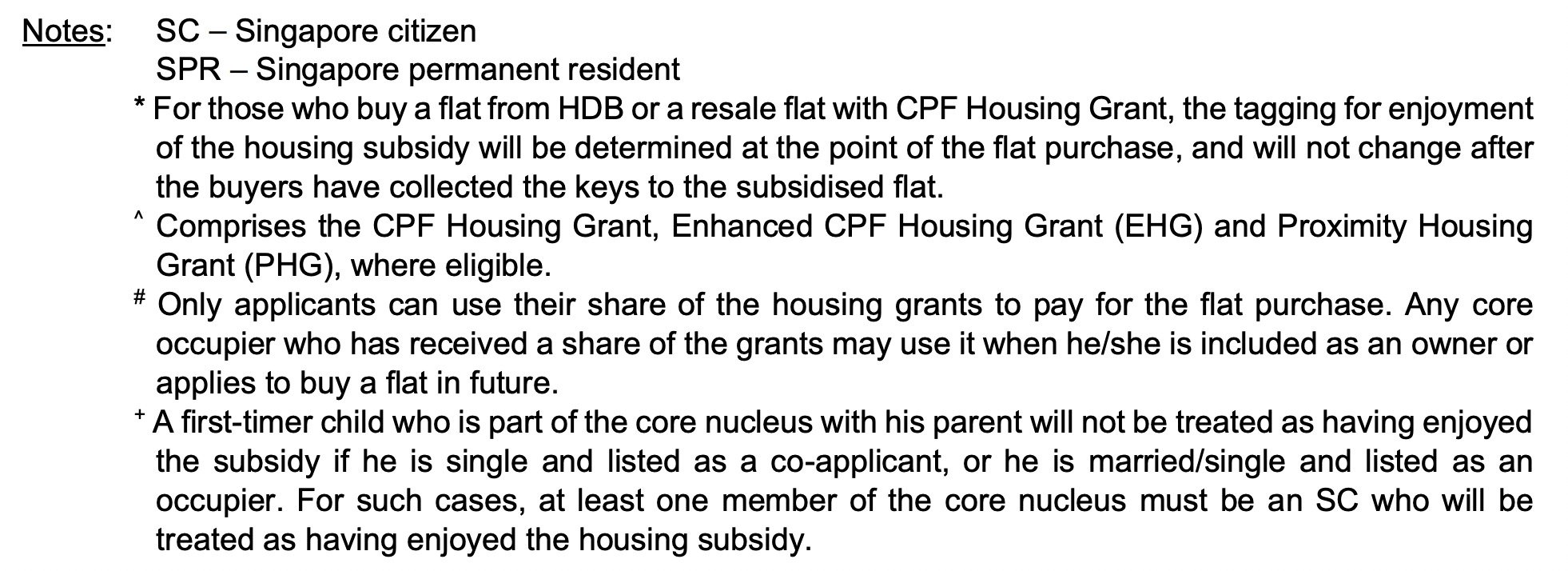

Just look at the application rate of BTO and SBF launches. The high application rates of second-timers should tell you how difficult it is to secure a flat as a second-timer.

What’s more, first-timer families get two more ballot chances, increasing their chances of securing a flat.

Another benefit of having one applicant as a first-timer is that first-timer/second-timer households can still enjoy grants, albeit less than households comprising two first-timers.

Meanwhile, second-timers generally aren’t eligible for any grants, unless they’re living in a subsidised 2-room flat in a non-mature estate or public rental flat, and buying a flat in a non-mature estate.

How it’s akin to a cooling measure

Treating the essential occupier as a second-timer makes it harder for them to get a BTO or SBF flat. Given the low likelihood, they may decide not to apply for a BTO or SBF altogether, reducing demand from second-timers.

As for the owner-essential occupier household, both parties will now be considered second-timers the next time they buy an HDB flat.

Perhaps more importantly, the implication is that there will be fewer first-timer/second-timer households (who will be considered first-timer families) joining the competition to get a flat.

But it will probably take some years before we see the impact. Since this change was only effective from 9 May 2023 onwards, there will still be groups of people (who were not impacted by the rule change) that may decide to take part in the balloting (as first-timer families) to get their second subsidised housing. If it’s any consolation, it’s that the number of people who can do this will eventually decline.

Planning to sell your HDB flat soon? Let us help you get the right price by connecting you with a premier property agent.

If you found this article helpful, 99.co recommends Sale of Balance Flats 2023, What you need to know about HDB’s Sale of Balance Flats (SBF) in 2023 and HFE (HDB Flat Eligibility) letter: What is it and how to apply.

The post Are the changes in distribution and use of HDB grants a form of cooling measure? appeared first on .