Did you know that in the early 1980s, condominium security was so lax that visitors can simply walk past security guards with a smile and use the swimming pool? Or that if you were driving a fancy car like a Mercedes-Benz without a resident label, the guard may mistake you as a resident and lift the gantry for you without question?

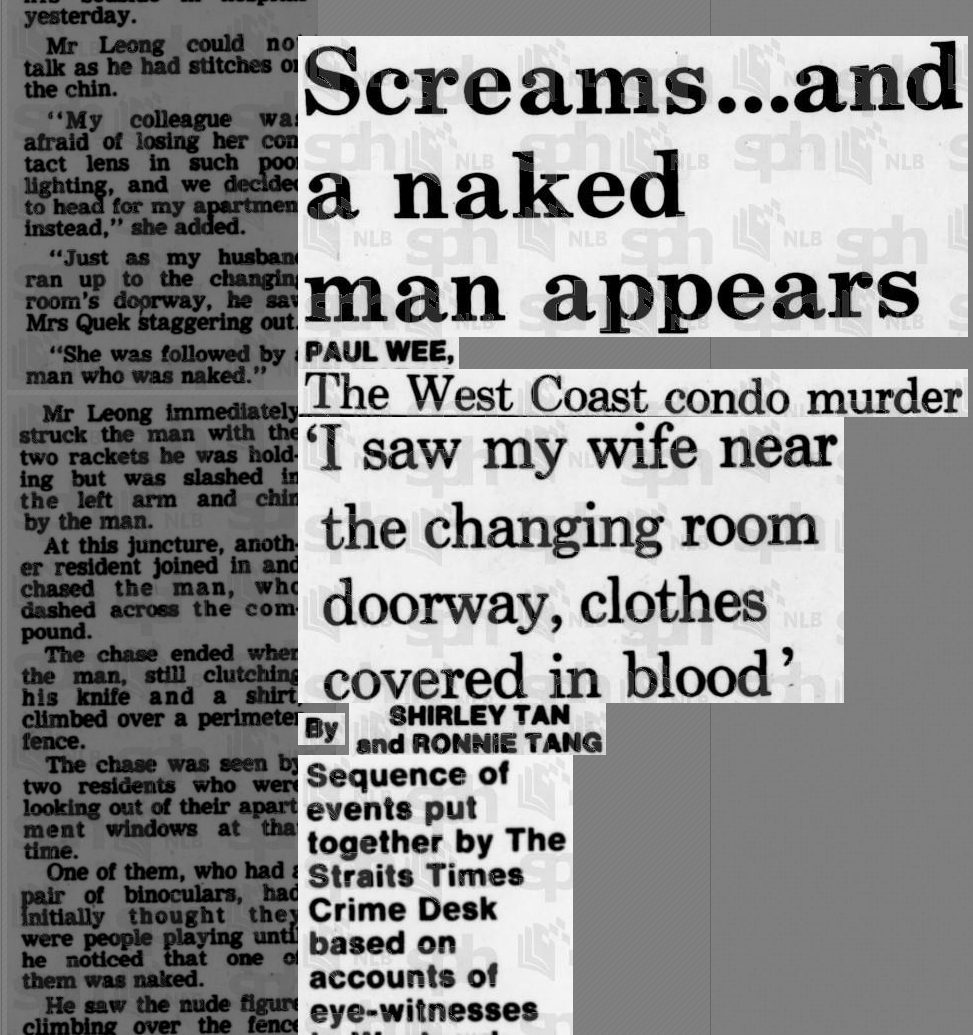

This changed 37 years ago in September 1984 when a woman, engineer Judy Quek (30), was stabbed to death after a swim at the 26-storey Westpeak Condominium in West Coast Road, Clementi. She and her husband had just moved into the condo four months ago.

That night, while her husband, nephews and niece were still in the pool, Judy had stepped out and gone to the ladies’ changing room, which, at the time, did not have key card security.

Unbeknown to her, the killer, a non-resident who had been swimming in the same pool earlier, tailed her. When his advances weren’t reciprocated, the naked man slashed and stabbed her with a knife.

After a chase and scramble with residents, the nude killer escaped over a wire fence and fled on a bicycle. The 27-year-old man was later apprehended and found to be suffering from schizophrenia. He was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1989.

Known as the West Coast condo murder, the case shocked Singapore residents, especially those living in condominiums and high-rise apartments.

Despite round-the-clock guard security at the condo, there were only two guards on duty each time – one at the main gate and another at the reception hall.

Residents complained that people had been taking shortcuts through the condominium compound from the adjacent HDB blocks to the Clementi Sports Complex nearby. Though the back gate had a lock, some residents claimed it was usually not closed.

After a review of the condominium’s security, the nine-member management committee of Westpeak Condominium added barbed wire on their perimeter fencing and increased the number of guards per shift from two to three.

Further reports of other condominiums then revealed that while some of them do issue security cards to residents, they were hardly used because the barriers were usually lifted and rear gates were always left unattended and open.

The issue of condominium security soon became widespread, as jittery residents, who were paying between S$173 to S$600 in monthly maintenance and security fees then, clamoured for improvements in their own condominiums.

Condo management committees (ie. MCSTs) had to work with their residents to tighten security. This meant making sure that residents’ visitors must have their identities and bags checked at all entry points, despite the inconveniences. To use their facilities, residents had to show passes to get into the swimming pool and squash courts.

In fact, at that time, Sommerville Park, a freehold condominium off Holland Road since 1978, sold itself as ‘one of the most secure condominiums in Singapore’ with at least 14 guards on patrol. The condo is sprawled across almost 900k sqft of land with just 456 units, so one can imagine the concerns then.

By the mid-1980s, as the Judy Quek murder trial continued, the Singapore police force started a two-year crime prevention exercise called “Ops Condo”. The intent was to identify common weaknesses in condominium complexes and highlight them as potential crime risks to MCSTs and residents.

While public housing estates had crime prevention activities at the grassroots and neighbourhood police level, private housing estates did not. Worrying still – there were 745 burglaries, 45 robberies and 20 rape cases in private housing estates in the first nine months of 1984 alone.

“Ops Condo” saw the police highlighting weaknesses like overgrown shrubbery along fences and dimly-lit walkways, which were “excellent foliage for house-breakings, robberies and rapes.” Flimsy perimeter fencing was marked as easy defences for criminals to escape, as was the case with the Judy Quek murderer.

Recommended measures included improvements to visitor checks, proper locking systems at entry points, metal door grilles, burglar alarms and keeping the lights on along the perimeter, car park and rear of buildings at night. CCTVs, digital locks for changing rooms and individual lift keys for residents were also added.

Over two years, police officers visited 216 condominiums and high-rise apartments, right up to individual homes.

They set up neighbourhood watch groups among residents and educated them on security awareness. Residents and residents’ associations can request the police to conduct security surveys of their compound and identify further weaknesses based on the implemented measures.

With the police’s help, informal neighbourhood watch groups were formed where residents kept an eye out on their neighbour’s property. Addresses and phone numbers were shared so neighbours can contact one another if they noticed anything suspicious.

By the early 1990s, condominium security had become far more sophisticated. Automated gates, multiple closed-circuit cameras and intercom systems were implemented. For the latter, guards would intercom residents, asking them if they were expecting visitors before letting them through.

Today, the guards don’t do that, but visitors including contractors and goods delivery riders can intercom residents directly from the lift lobby once the guard has taken their identities and allowed them through the main gate.

Wherever we live, be it in HDB flats or private condominiums, we so often take housing estate security for granted, especially if crimes in the neighbourhood don’t affect us. At least now, as we understand how these security improvements came about, and why they’re important, we probably should appreciate them more.

You can watch a reenactment of the murder and case trial from meWatch’s True Files (hosted by Lim Kay Tong) here. Viewer discretion is advised:

–

What are your thoughts on your condominium security? Let us know in the comments section below or on our Facebook post.

If you find this article helpful, 99.co recommends 5 safe distancing measures deployed by the MCST or MA at condos other residents may not know about and The 7 types of condo security guards in Singapore.

Looking for a property? Find the home of your dreams today on Singapore’s fastest-growing property portal 99.co! If you would like to estimate the potential value of your property, check out 99.co’s Property Value Tool for free. Meanwhile, if you have an interesting property-related story to share with us, drop us a message here — and we’ll review it and get back to you.

–

What happened in the West Coast condo murder?

In September 1984, a woman, engineer Judy Quek (30), was stabbed to death after a swim at the 26-storey Westpeak Condominium in West Coast Road, Clementi. She and her husband had just moved into the condo four months ago.

How did the West Coast condo murder changed condominium security?

The case, known as the West Coast condo murder, shocked Singapore residents, especially those living in condominiums and high-rise apartments. Despite round-the-clock guard security at the condo, there were only two guards on duty each time – one at the main gate and another at the reception hall. Residents also complained that people had been taking shortcuts through the condominium compound from the adjacent HDB blocks to the Clementi Sports Complex nearby. Though the back gate had a lock, some residents claimed it was usually not closed. After a review of the condominium’s security, the nine-member management committee of Westpeak Condominium added barbed wire on their perimeter fencing and increased the number of guards per shift from two to three.

What else happened in terms of condominium security after that?

By the mid-1980s, as the Judy Quek murder trial continued, the Singapore police force started a two-year crime prevention exercise called “Ops Condo”. The intent was to identify common weaknesses in condominium complexes and highlight them as potential crime risks to MCSTs and residents.

The post How a West Coast murder in 1984 changed condominium security appeared first on 99.co.