Being in land-scarce Singapore has its challenges, so it comes as no surprise that besides building ever taller (and more compact) apartment buildings, we’re also looking at building (downwards) deep underground and (outwards) at sea.

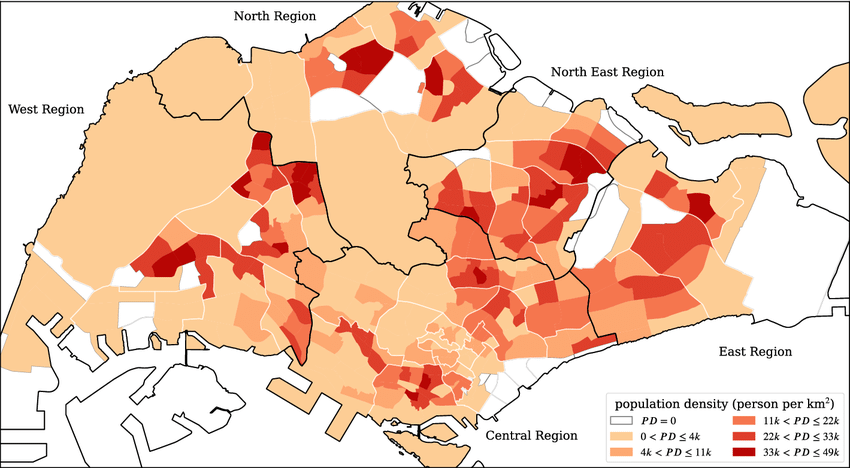

In just four decades, Singapore has gone from being an urban slum to a thriving global city-state. As a densely populated metropolis today (5 million+ people across 710 km2 of land), Singapore is one of few high-density cities with high liveability standards. Question is: how long do we have before we run out of land? And then what?

Also, with the spectre of another pandemic-level event like SARS and COVID-19 impacting cities with denser population sizes, wouldn’t it make better sense to spread our population density just a bit wider? At least, if not during our time, then for our children’s and grandchildren’s sake?

Under the Land Use Plan 2030, the Ministry of National Development has allocated and safeguarded Singapore’s surface land space for industrial and commerce (17%), transport infrastructure (13%) and utilities (3%), all of which require a substantial amount of land. But an additional 5,600 hectares of land will be needed by 2030 to cater for the increased population.

Singapore has also successfully combined highly dense urban structures with high living standards, proving that high-density living doesn’t mean compromising on the quality of life. However, to meet our urban environment’s many and growing needs, some of these uses can be moved underground.

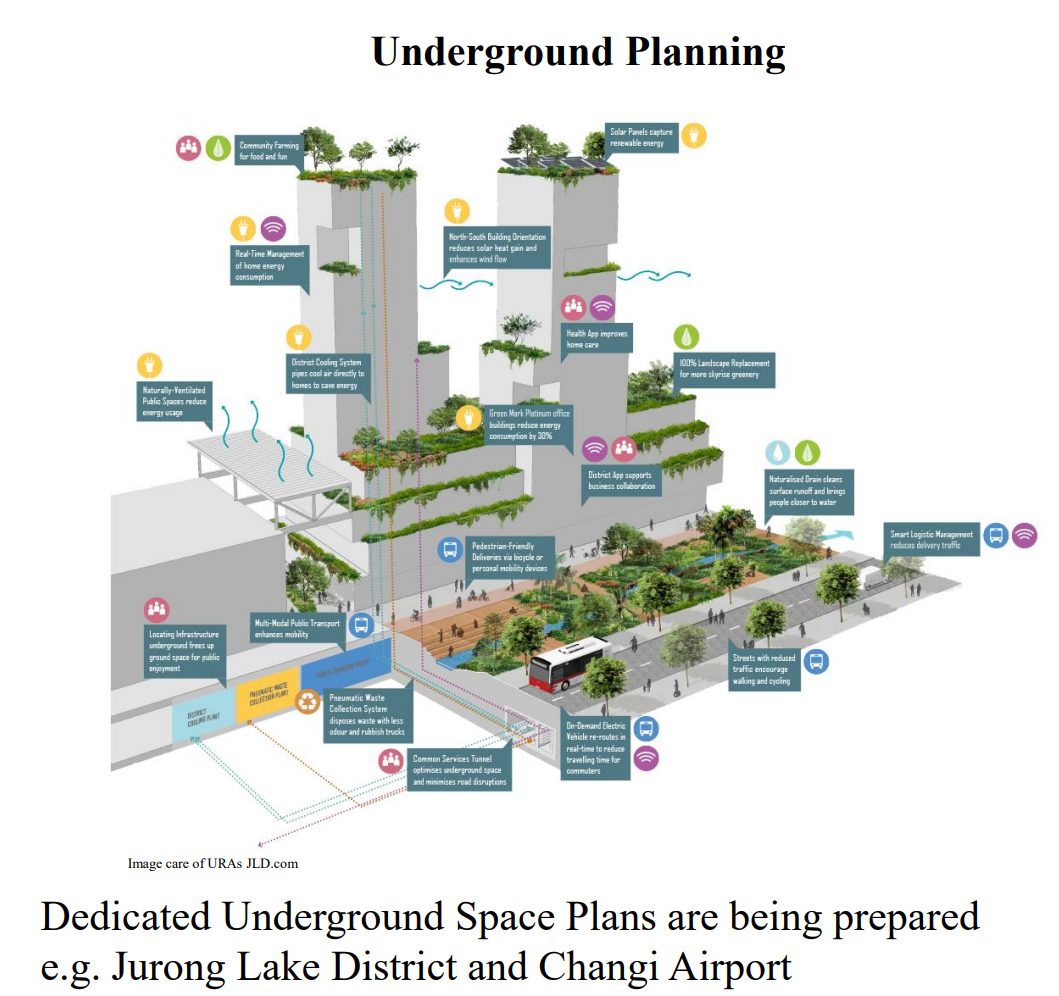

While there are no plans to put homes or offices underground, the strategy is to use subterranean space for infrastructure. The subsequent freed up land can then be used for housing, community uses, and greenery at the ground level.

While the rest of the world has precious raw materials such as gold, oil or diamonds, Singapore’s most precious commodity (or lack thereof) is island space. Being a tiny country, Singapore has been reclaiming land from the sea since its first reclamation in 1822 on Boat Quay, using it to build many famous creations, including Changi Airport and the current CBD area.

But now, with the ongoing global warming crisis, rise in sea levels and other impacts of climate change, reclaiming land and expanding our borders in that manner is not going to be possible or sustainable for much longer. Moreover, reclamation has become more expensive as it moved to deeper waters, while countries that used to sell sand to Singapore have stopped exports also.

But something needs to be done for Singapore’s central government to meet its ambitious goal of growing the population to 6.9 million by 2030 for economic growth and to keep up with GDP objectives. That means somehow finding space to fit another 1.3 million residents on the island that is already resembling a densely packed Hong Kong.

Singapore has successfully managed its rapid growth in recent decades by expanding outwards and building into the sea or upwards by constructing high-rises. It has avoided the usual overcrowding and traffic problems common in other fast-developing Asian countries metropolises.

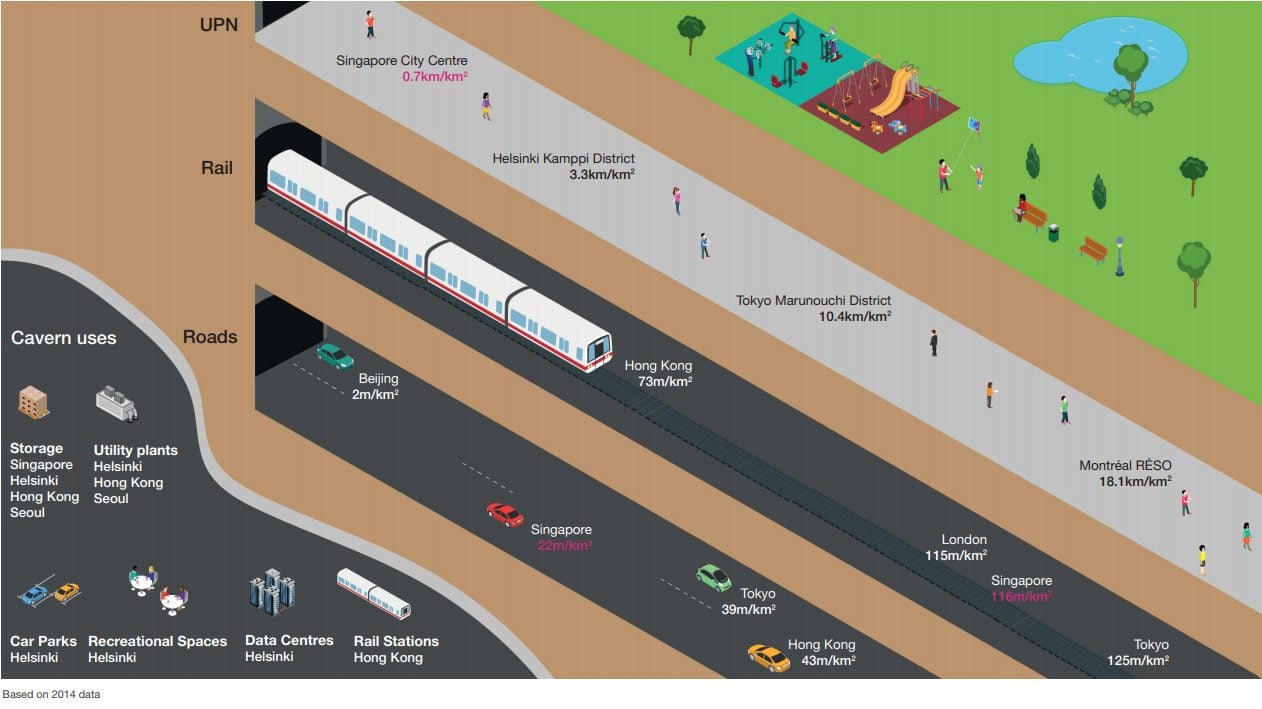

Part of the solution lies in going underground. Why grow out when you can grow down? Globally, underground spaces have been widely used to house industry, utility and transport infrastructure in the heart of urban areas to reduce their negative impact on city living.

Creating space underground may be new to Singapore, but it has been part of Scandinavia’s core growth strategy since the 1960s. Montréal has had an underground city since 1962 and Helsinki is home to an entire underground city that houses everything from hockey rinks to a church.

The underground city doubles as a training ground for the Finnish army by digging into its stable bedrock. The subterranean warmth is also helpful in heating the underground swimming pools. Even Hong Kong has been making significant progress with its underground expansion plan, winning the 2020 ITAA International Tunneling Association Awards for its proposed network of underground storage caverns.

Fortunately, Singapore is also becoming a global leader in this growing trend or underground urbanism movement thanks to its subterranean master plan and a hefty investment of $188 million in underground technology R&D.

Some assets that government planners have moved underground include the world’s largest district cooling system; a water reclamation system; ammunition for the Singapore Armed Forces; a 23-mile tunnel system to move goods between two aboveground industrial estates; and adding another 113 miles of rail network (essentially doubling the size of our rail network by 2030).

To support prioritising underground infrastructure, 2015 saw the government make legislative changes to enable it to buy land beneath private blocks, and limit private owners to 30 metres of space below their properties, giving homeowners ownership of only the underground space up to their basement, allowing the government to use the deeper land without facing private property issues.

Moving facilities underground has advantages beyond saving space, including reduced use of air conditioning which could save energy in Singapore’s tropical climate. Interestingly, Singapore is Southeast Asia’s first underground facility for storing liquid hydrocarbons. Going 130m deep under the seabed to build a 9-storey tall cavern has freed up 60 ha of surface land (large enough for six petrochemical plants).

To put utilities, transport, storage and industrial facilities underground, and free up land on the surface, Singapore is using 3D technology to produce subterranean maps for the country’s masterplan. Piloted in 2019 as part of URA’s next Master Plan, it was a way to look at the island’s existing underground spaces and infrastructure for industrial, commercial, residential and green space uses in Singapore.

“Given Singapore’s limited land, we need to make better use of our surface land and systematically consider how to tap our underground space for future needs,” said Ler Seng Ann, a group director at the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA).

“Currently, our focus is on using underground space for utility, transport, storage and industrial facilities to free up surface land for housing, offices, community uses and greenery, to enhance liveability,” he said. The Underground Master Plan will feature pilot areas, with ideas including data centres, utility plants, bus depots, a deep-tunnel sewerage system, warehousing and water reservoirs.

The 3D model of “Virtual Singapore” has been created to assist in everything from urban planning to disaster mitigation, as 3D technology allows the visualisation of space that otherwise cannot be seen. Currently, there are no plans to move homes or offices below ground (despite the headline).

One of the most ambitious underground projects in Singapore is a system that pumps chilled water through pipes to cool buildings around the city’s famous waterfront district of Marina Bay.

According to Foo Yang Kwang, the chief engineer of Singapore District Cooling, SP Group, facilities that use this centralised system, rather than relying entirely on their air conditioners, have reduced energy consumption by around 40 percent. Subsequently, the reduced energy use has enabled the buildings to slash their annual carbon dioxide emissions by 34,500 tonnes (think taking 10,000 cars off the road).

Besides space constraints, Singapore’s unfavourable weather is another motivator for tapping into underground space to help avoid the rising heat, humidity and increasingly heavy rainfall. Furthermore, utility networks are subject to more wear and tear in these conditions, so placing them underground is a more viable option.

But since building underground is generally more expensive and complex than on the surface, moving infrastructure and other facilities underground is often considered a last resort only when surface space is exhausted, and no other options exist due to the high costs associated with it. Mr Chintan Raveshia from planning, design and engineering consultancy Arup said city planners and designers should remember to make cities feel like home even as they plan for them to be “fit for many futures”.

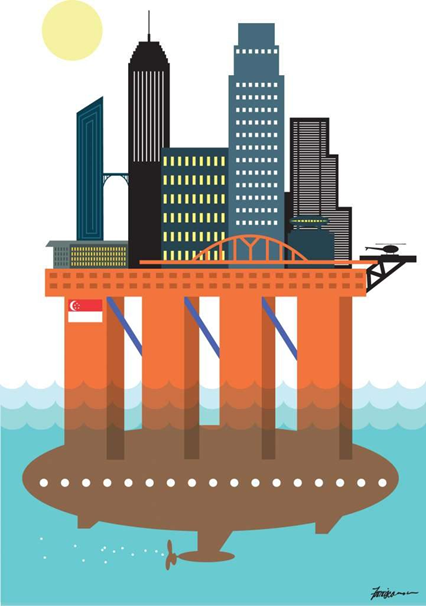

While we forge ahead with our underground strategy, plans are underway to build and expand outwards at sea. Keppel Corporation is at the forefront of exploring nearshore urban developments to build a floating city in Singapore.

Keppel chief executive officer Loh Chin Hua said, “We have the technology and capabilities to build floating cities which can address both land scarcity as well as the threat of rising sea levels in coastal areas.” In China, for instance, the government has already built a network of sponge cities to tackle urban flooding and water scarcity issues that may result from climate change, which bodes well for us too, if we can better prepare for disruptions from pandemics and climate change in a similar manner.

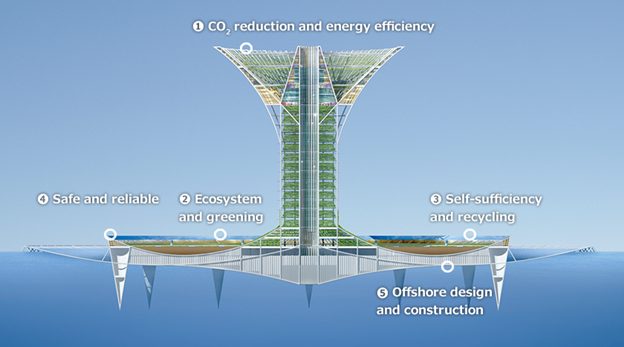

Indeed, a floating island and apartments perched over roads and old buildings is a potentially viable option for Singapore to overcome its land shortage. Construction giant Shimizu Corporation is working on building the Green Float, a floating city for upwards of 50,000 people in Singapore, with homes at the top, offices in the middle, vegetable farms at the bottom and beaches around it.

“The technology required could be realised here and now,” says Mr Shinichi Takiguchi, managing executive officer at Shimizu’s Emerging Frontiers Division. “I won’t have to wait till my grandchildren’s generation. I’ll be able to see it while I’m still alive.”

Interestingly, building the Float would cost as much as reclamation. It is expected that the Green Float will take approximately ten years to construct, with a 1-km-high tower and a 3km (diameter) base. Once completed, it is expected to last 100 years.

At Shimizu’s Institute of Technology in Tokyo, scientists have already achieved breakthroughs in creating suitable concrete for sea-based structures, including buildings. And Singapore’s calm equatorial waters may be one of the best places in the world for them to construct a Green Float. “The wind and water currents around Singapore are much weaker in comparison to Japan. Thus we can safely say that safety won’t be a concern,” says Mr Takeuchi.

Imagine that in the future, thinking about a BTO flat built on a float at sea or suspended over a canal might not be such a far-fetched idea at all.

Underused land potential also lies in adding new levels above shophouses and using drainage canals, which are only helpful during heavy rainfall. But at all other times, they’re an expensive wasted land resource and unused land space, on which apartments could potentially be built.

According to Mr Michael Shaw, the director of Pent Developments, who develops rooftop homes in London, a frame laid over a canal would form the support structure for apartments with modular components made in factories. According to his plan, each development would have six storeys and 60 units of various sizes, from one to three bedrooms. “You do not have to buy the land, and that’s a huge saving. So even if the construction method is slightly more expensive, the overall savings would be huge.”

Equally, the space above roads could be just as productive. An expressway running through Hamburg is getting roof covers that will be turned into land for parks and other facilities while simultaneously connecting communities separated by the expressway.

Singapore already took advantage of this idea of building over significant roads with the S$16 million Eco-Link@BKE, which opened in 2013 to restore the ecological connection between the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve and the Central Catchment Nature Reserve. In future, such bridge-like structures might be a way to inject new spaces into business districts, serving as areas on which low-rise offices or community facilities could stand.

Indeed, the future looks bright and exciting for our upcoming generations when Singapore is at the forefront of such innovation and dynamic creations despite being a country short on land for its ideal purposes. If such novel living spaces and rejuvenation ideas can be successfully designed and implemented in other land-scarce cities, there is no reason that the same can’t happen in Singapore.

Watch this space.

–

Will you want your future generations to live underground or out at sea? Let us know your thoughts in the comments section below or on our Facebook post.

If you found this article helpful, 99.co recommends More condo sites released for H1 2021: Here’s what it’s like living there and 7 reasons Singapore continues to be a safe haven for foreign property investors.

Looking for a property? Find the home of your dreams today on Singapore’s fastest-growing property portal 99@co! If you would like to estimate the potential value of your property, check out 99.co’s Property Value Tool for free. Meanwhile, if you have an interesting property-related story to share with us, drop us a message here — and we’ll review it and get back to you.

The post Would you be willing to live underground or out at sea if we ever run out of land? appeared first on 99.co.